Healthcare worker stress is a huge problem that needs to be addressed or staffing is going to reach a crisis level.

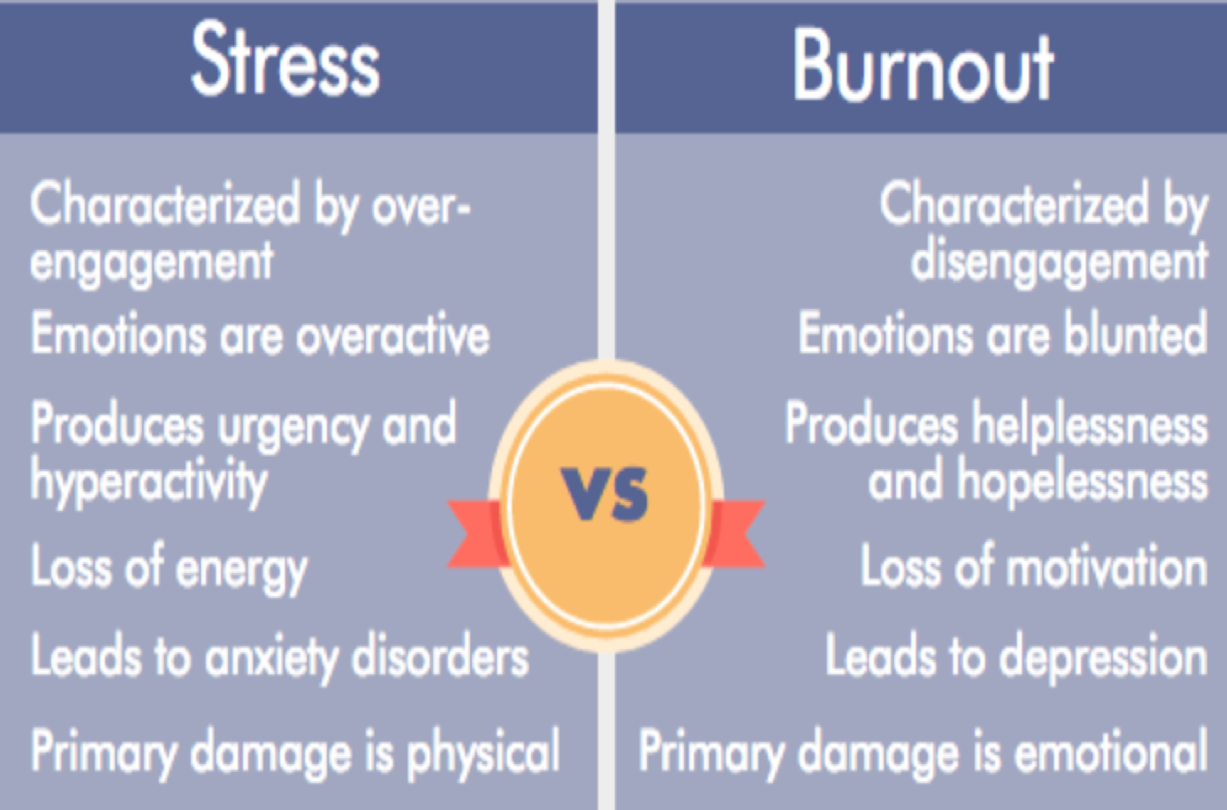

First, a definition of terms. Stress and burnout are sometimes used interchangably, but they are distinctly different.

Pandemics & HCW

The toll of pandemics on HCWs is significant given their duration

During major epidemic outbreaks, demand for HCWs grows even as the extreme pressures they face cause declining availability.

During an outbreak, HCWs are expected to work long hours under significant pressure with often inadequate resources, while accepting the dangers inherent in close interaction with ill patients and emotional fatigue.

HCWs, like everyone else, are vulnerable to the disease itself and to rumors and misinformation/disinformation especially from political leaders which leads to both an increase in anxiety levels and a growing sense of moral distress.

ways COVID-19 effects emotional (and mental) wellbeing of HCWs

- Environmental stress: working in an environment of risk without a sense of PPE protection, stress of seeing pubic not wearing masks in our presence when requested to do so as a civic duty, i.e. not following rules, etc.

- Anticipatory anxiety: are the symptoms I am experiencing signs of COVID-19 or signs of a cold, allergies, some other illness.

- Anticipatory distress: I have someone I am responsible for caring for with a precondition or who is in the highest risk age group, and I have to work in an environment of risk engaged in essential services, and/or to support my family which is living on the margin.

- COVID-19 guilt: Have I infected my family with the virus, am I putting my family at risk today?

- Adopting an “at risk” role that is psychologically draining: being hyper vigilant leading to anxiety and paranoia.

- Caution fatigue: can not deal with having to be cautious all the time, longing for activities that define the person, contact with others that is sensorial etc.

- Depression associated with isolation. When physical distancing becomes social distancing, for example I can not see my grandchildren, or my mother who is in a care facility not allowing visitors.

- Social risk: fear of losing an existing or desired social relationship and even one’s sense of identity.

- Emotional cascade: associated with too much uncertainty in too many areas of life; no back up plan for employment, rent, etc.

- Emotional fatigue: from dealing with too much depressing and/or terrifying news about the disease and the state of the country leading to a sense of doom and dread.

- Emotional hollowness: associated with too much screen time and too little sense-based human contact. A sense of lack, or connection, a sense of dissociation, feeling of interacting that is two dimensional and not three dimensional.

- Sense of deep loss and vulnerability: psychological trauma of losing a colleague be it near or far.

- “Fuck it” syndrome: feeling this is all a bit much, I can’t live my life this way and deciding to take risks as a means of returning to a familiar or comfortable life. While also worrying about it or entering a state of denial that is challenged by others (significant others, colleagues etc.).

HCW and the Myth of the Hero

HCWs are generally givers, many find it difficult to ask for support. A “take charge” and “be in control” attitude is common among many HCWs.

HCWs are often represented as “superheroes” on the frontline in a war against COVID-19. While being heroes is gratifying, HCW are beginning to come forward and express feelings of vulnerability while working long hours in environments of high risk and high mortality.

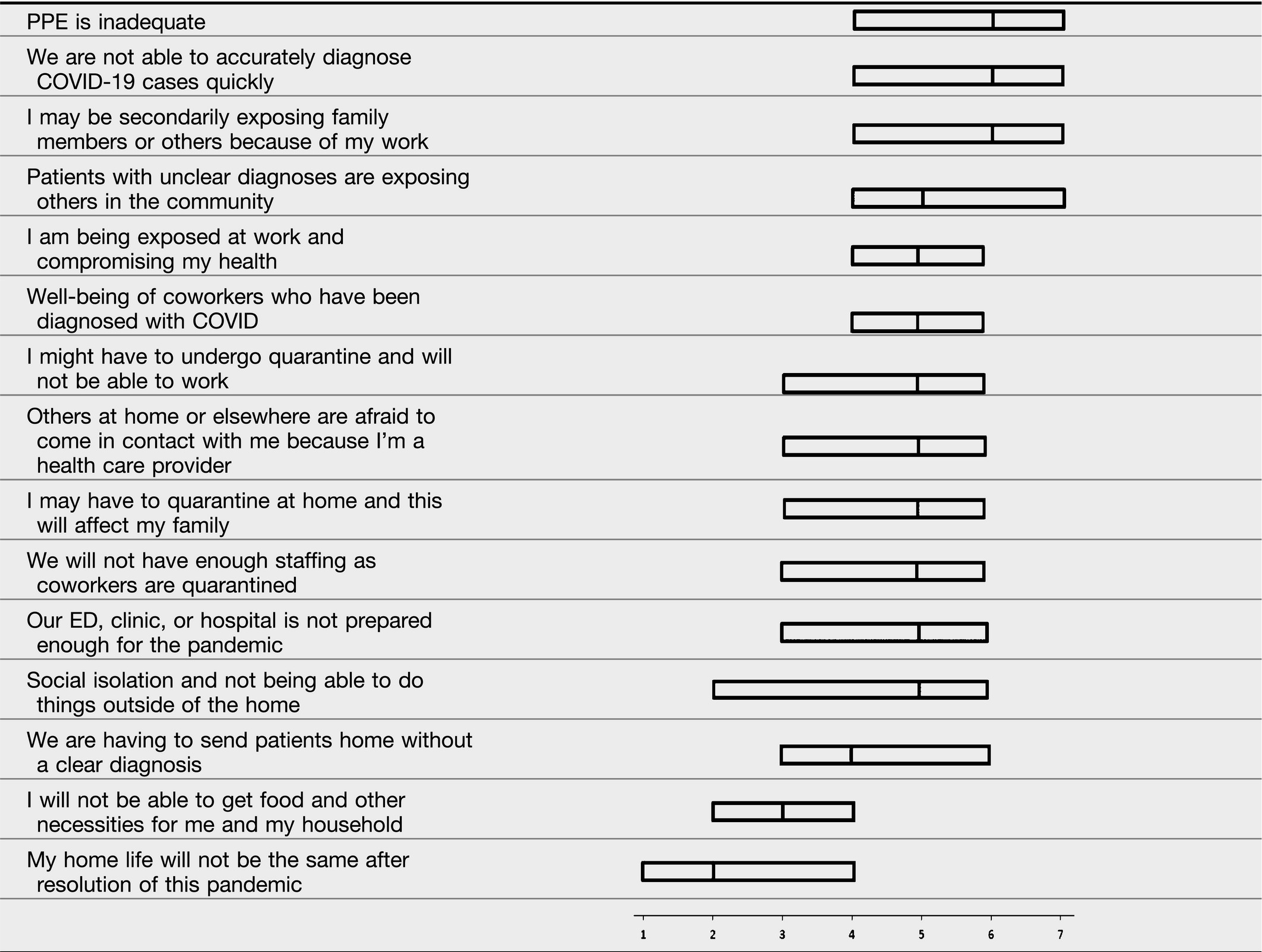

Emergency Room Doctor Survey, 2020

426 Emergency Medicine physicians were surveyed. On a scale of 1 to 7 (1=not at all, 4= somewhat, and 7= extremely), the effect of the pandemic on work and home stress levels was 5. Emotional exhaustion/burnout increased from 3 (pre-pandemic median) to a level of 4.

Most physicians (90.8%) reported changing their behavior toward family and friends, especially by decreasing signs of affection (76.8%).

Emergency physician ranking of stressors

Risk of infection to families: a constant source of worry for HCW

Under normal circumstances, HCWs usually have access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) to properly protect themselves from infection. The nationwide shortage of PPE has put HCWs at an even greater risk of acquiring COVID-19.

Persons infected with COVID-19 on the job can be asymptomatic and infectious and place their families and those they routinely interact with at risk. And on the other hand, family members of HCWs can place HCW at risk to spreading the virus to the patients they care for.

References

Rodriguez, R.M., Medak, A.J., Baumann, B.M., Lim, S., Chinnock, B., Frazier, R. and Cooper, R.J., 2020. Academic Emergency Medicine Physicians’ Anxiety Levels, Stressors, and Potential Stress Mitigation Measures During the Acceleration Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Academic Emergency Medicine.

Glenza J. US medical workers self-isolate amid fears of bringing coronavirus home. The Guardian. Published March 19, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2020.

Zhang J, Tian S, Lou J, Chen Y. Familial cluster of COVID-19 infection from an asymptomatic. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):119. Published 2020 Mar 27. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-2817-7