Burnout is a long-term problem for healthcare workers that has been exacerbated by COVID-19.

Burnout: a toxic occupational syndrome

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes burnout as one of the results of poorly managed chronic workplace stress that is characterized by three dimensions:

- Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job

- Reduced professional efficacy

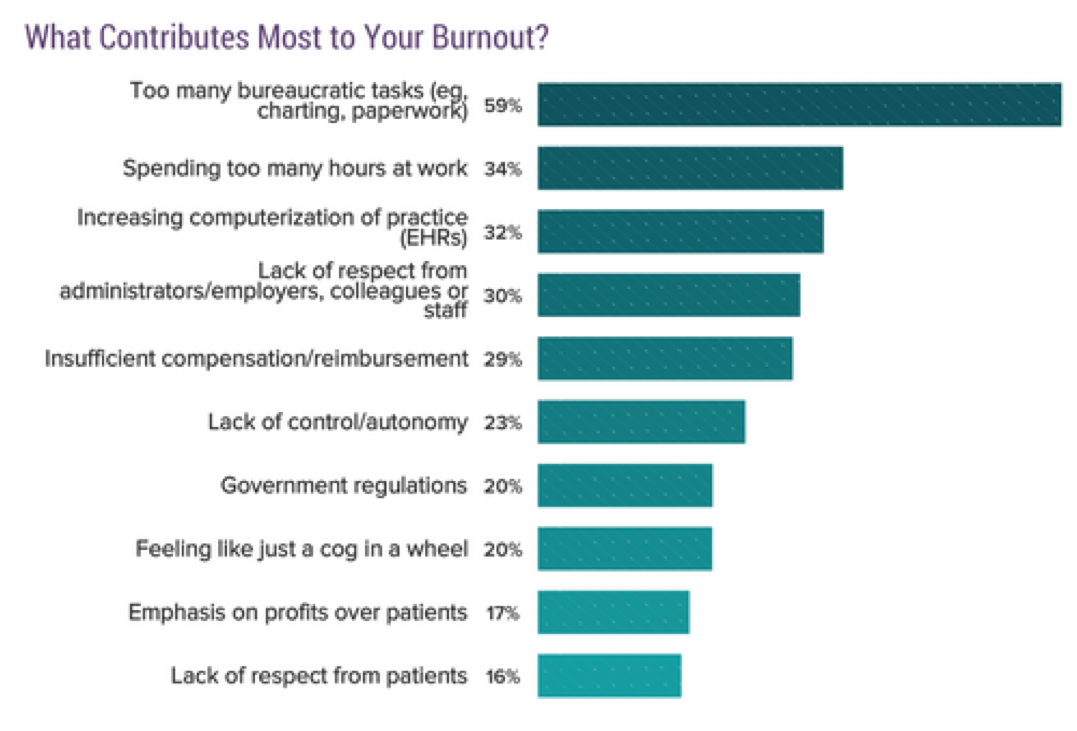

It is important to recognize that burnout is predominantly a systemic rather than individual psychological problem.

In other words, the problem isn’t the healthcare worker. It’s the system the healthcare worker is attempting to function within.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory crosses all workplace environments. The six realms include:

- Workload (too much work, not enough resources)

- Control (micromanagement, lack of influence, accountability without power)

- Reward (not enough pay, acknowledgement, or satisfaction)

- Community (isolation, conflict, disrespect)

- Fairness (discrimination, favoritism)

- Values (ethical conflicts, meaningless tasks)

Moral Distress

Moral distress is also a factor resulting in burnout.

Experiences of moral distress result from a perceived violation of one’s core values and duties, combined with a feeling of being constrained from taking ethically appropriate action.

Moral distress occurs when one believes one knows the morally right thing to do, but institutional and/or structural (governmental, employer, etc.) constraints or policies make it impossible to pursue the desired course of action.

In the context of COVID-19, an example of moral distress is a government policy that does not follow public health guidelines for COVID-19 and leads to surges of COVID-19 patients in hospitals–which then places healthcare workers at risk.

When healthcare workers speak out about the need to follow guidelines and are portrayed as impeding society returning to business as usual, they experience moral distress.

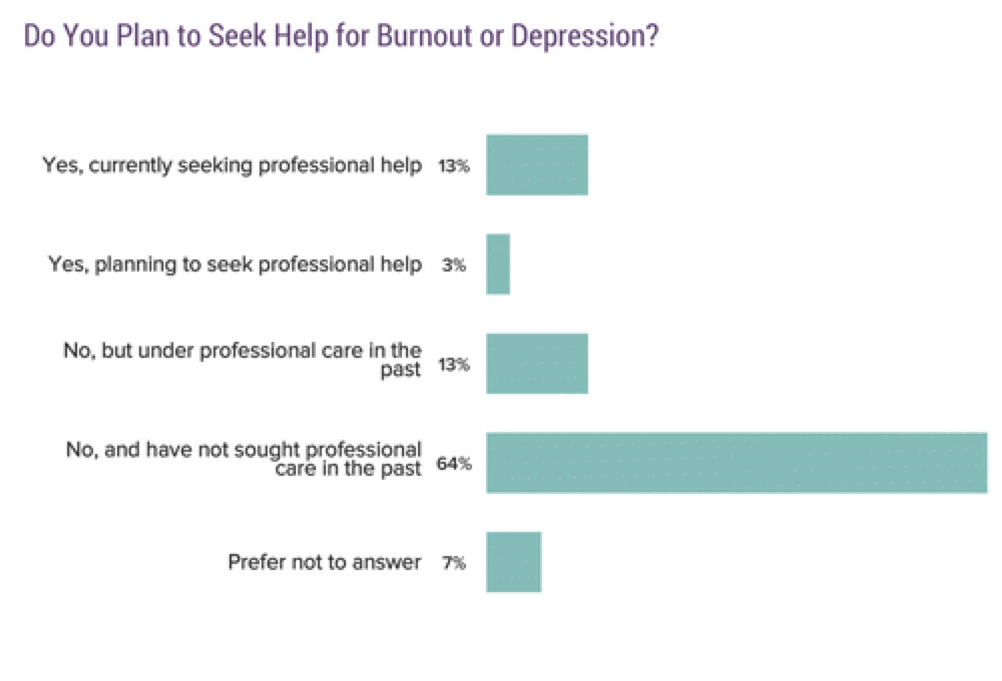

Healthcare workers who experience moral distress and its associated negative outcomes are more likely to leave front line positions and, in some circumstances, leave the profession entirely.

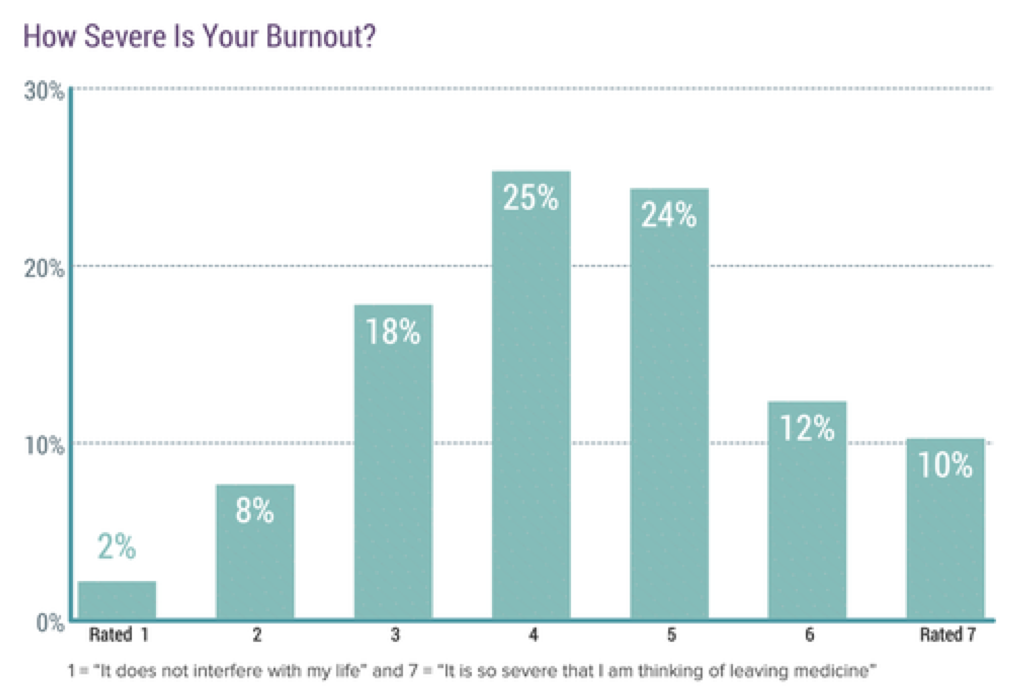

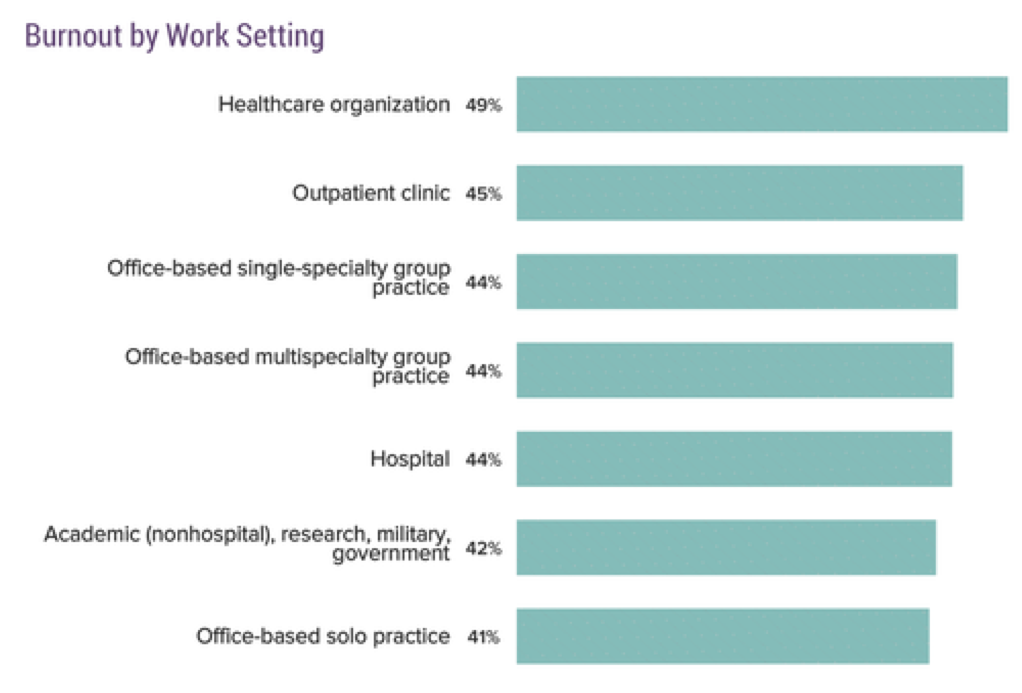

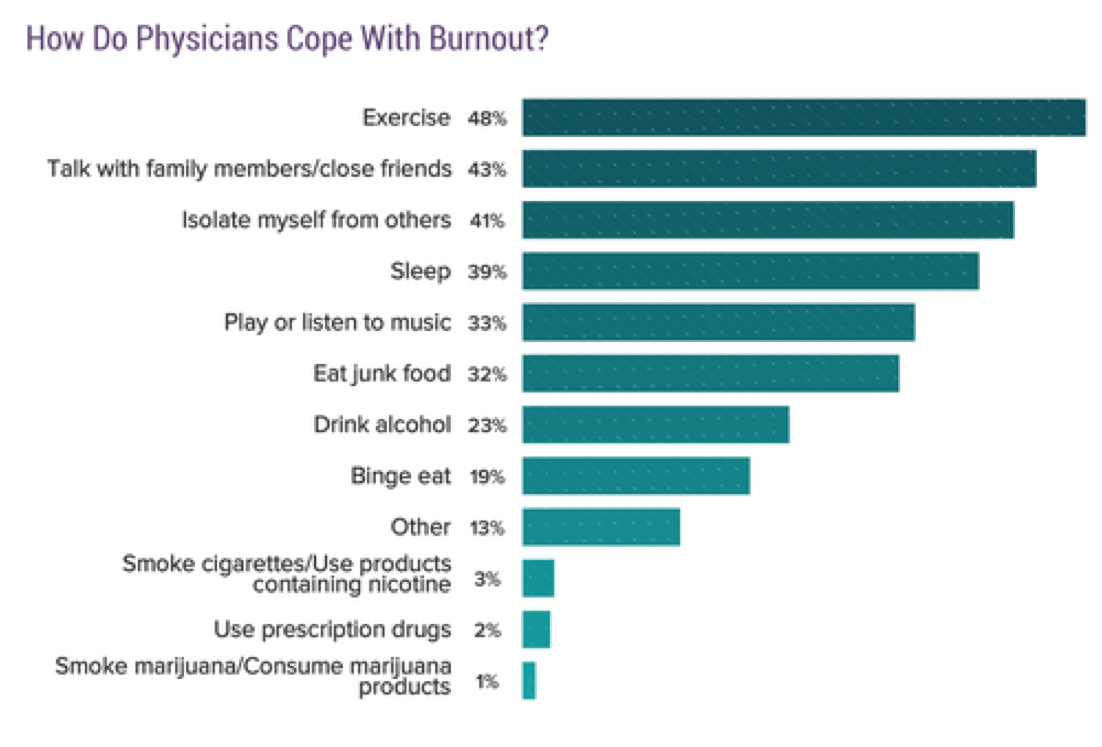

Graphs in this post are from the Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020, which surveyed more that 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties.

Burnout prior to COVID-19

Before the pandemic hit, 42% of more than 15,000 physicians who responded to an online survey by the medical news website Medscape reported feeling burned out.

High rates of depression and suicide in the medical profession have long been a problem.

The pandemic is exacerbating a systemic problem and we are seeing the fault lines of a health care system long in need of reform

The nationwide physician burnout rate was 51% (50-69% range) (2017).

Registered Nurses and Physician Assistants reported 37% burnout rates (2011).

Residents and Med Students (2016) reported a 69% overall burnout rate: 78% among surgical residents; 68% non-surgical.

36% of U.S. physicians, as compared to 61% of other U.S. workers, are satisfied with their work-life balance.

%

Burnout rate of Physicians under 35

%

burnout rate of critical care physicians

%

burnout rate of emergency medicine physicans

%

How much higher the burnout rate is for female physicians

%

of physicians report being over-extended or at full capacity

%

of doctors plan on reducing patient service

Nurse Burnout during COVID-19

A recent nationwide survey of nurses revealed the emotional toll of the COVID-19 pandemic.

%

of nurses experiencing unprecedented levels of physical, emotional, and mental stress

%

of nurses likely to leave their current position or specialty

%

of nurses planning to leave their facility or leave the healthcare industry

94% reported needing peer support groups, mental health counseling, or financial assistance at this time.

Importantly, many nurses participating in the survey also reported feeling burned out.

management priorities

A study of workforce engagement during COVID-19 highlights management priorities for addressing healthcare worker burnout.

Study findings reflect cultural strengths of health care organizations and their personnel who have risen to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, the data also reveal that segments of the health care workforce vary in the extent to which they feel that teamwork, communication, and support are ideal.

Front-line nurses and other clinical professionals caring for COVID-19 patients are especially likely to express concerns about teamwork, communication, and support.

The importance of addressing systemic factors that lead to burnout

Systemic factors play a major role in fostering burnout. When those factors are indentified and addressed, they can be a powerful powerful antidote to burnout.

The most powerful interventions to reduce burnout apply an ecosystem approach that improves workplace safety and satisfaction, workflow efficiency, teamwork, and leadership.

References

World Health Organization. Burnout.

Maslach & Leiter, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Maslach Burnout Inventory

Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2020: The Generational Divide

Medscape Lifestyle Report 2017: race and ethnicity, bias and burnout. [May;2018 ];Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2017. https://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2017/overview Accessed. 2017 11:2013.

Shanafelt, et al. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, December 2015, Vol 90, Issue 12

Nurses’ widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, Sloane DM, Aiken LH Health Aff (Millwood). 2011 Feb; 30(2):202-10.